When our generational cover is blown we inherit the family legacy. The sober moment when our last aged parent dies leaves us blinking in the sunlight of mortality. We become the keeper of the family legacy.

When our generational cover is blown we inherit the family legacy. The sober moment when our last aged parent dies leaves us blinking in the sunlight of mortality. We become the keeper of the family legacy.

The business of managing the family legacy extends beyond organizing our parents’ archives and dispersing their assets. We are now the family matriarch or patriarch. If we choose to shoulder that responsibility, we become the moral compass of the family. And although we cannot claim to know all truth, we do have something to say based on our seniority.

Shaping and sharing the family story can be a heavy obligation to avoid, or an opportunity to contribute something of value to future generations. With the wisdom of our years, we recognize that deciding what to say, how to say it and, most important, when to speak is a challenge.

That the stories vary with each teller is, in itself, instructive. Matriarchs and patriarchs most likely speak the similar truths, but in different fashion. The important point is that we are the caretakers of the family story. Our understanding of our family history and the understanding of generations to come is within our power to shape.

Collective wisdom

Collective wisdom holds that our memories of our forbears go back three generations. But genealogy records now grant us access to ancestral events that go back further than that. We can use these unfamiliar stories to help us understand who we are.

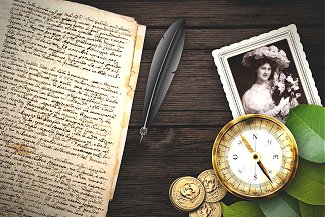

As memory custodians, we can only tell our stories in three ways: As they were told to us; as we experienced them; or as we have managed to piece together from records, anecdotes and photographs.

Accuracy we leave to the historians. Our purpose is to keep the family legends alive. Our privilege is to offer our own unique perspective in the hope that our stories will be useful as well as entertaining. After all, some of our fancies and foibles are coded into our DNA.

Research finds that individuals who are, for example, artistically creative have a specific genetic characteristic that may enhance their creative ability. To know that we may have inherited artistic or musical talent encourages us to believe our pursuit of such an interest might be successful. What a lovely legacy.

A piano stood in my parent’s living room. On a blonde wooden Baldwin, My mother practiced the pieces she would play to help young dancers in my grandmother’s ballet studio keep rhythm. I practiced my piano lessons on that piano. When my granddaughter began music lessons, I shipped it to her, along with now antique music books. I told her the stories of her musical heritage. Many years later, she shows promise of exceeding the accomplishments of the musicians that went before her.

On the other side of this coin, to realize we might have a genetic leaning toward less desirable behaviors, such as short temper or substance abuse, empowers us to address weaknesses.

I was raised to believe we had Native American blood. That supposed fact, the Irish my husband was said to have brought to the mix, and the stories we heard about alcoholic relatives led us to caution our children. We told them they might be susceptible to addiction. As it happens, DNA testing proved my Cherokee roots nonexistent and my husband’s Irish heritage greatly exaggerated.

We had to recant. No regrets, though. Our children developed the habit of moderation. The truth is, these legends and myths existed somewhere in the minds of our ancestors and deserve the telling. The light of new knowledge adds the element of mystery to some family stories.

Telling our stories

What’s your story? How will you tell it? Charting a family tree may provide a reasonably accurate record for future generations, but sketching the leafy branches in story form is far more revealing.

At first glance, your tree may appear to be a uniform sample of its species. But move your gaze through its branches and you will likely find broken limbs and odd grafts. This is a storyteller’s gold; a writer’s eureka.

A well researched biography (non-fiction) captures the facts. A masterful storyteller, David McCullough for example, informs us of verifiable historical events in a compelling way. But there are other ways to leave a legacy in written form.

Memoirs—the telling of personal and family stories— are riding a wave of popularity. The genre acknowledges that the accounts are subjective, drawn from memory and told from a unique point of view.

Family sagas are an intriguing mix of fact and fiction. To tell a good story historical fiction writers have to make up what they don’t know. Digging into ancestral records can raise facts that help shape a story, but it won’t be strictly accurate. And it doesn’t need to be.

Leave a Reply